Rediscovering the creative self: Clare Ormsby’s Fallowfield is currently running at ArtHouse Jersey at Capital House

Pictured: Artist Clare Ormsby at the opening of Fallowfield at ArtHouse Jersey at Capital House. Taken by Max Burnett.

Visit the full Fallowfield exhibition page here

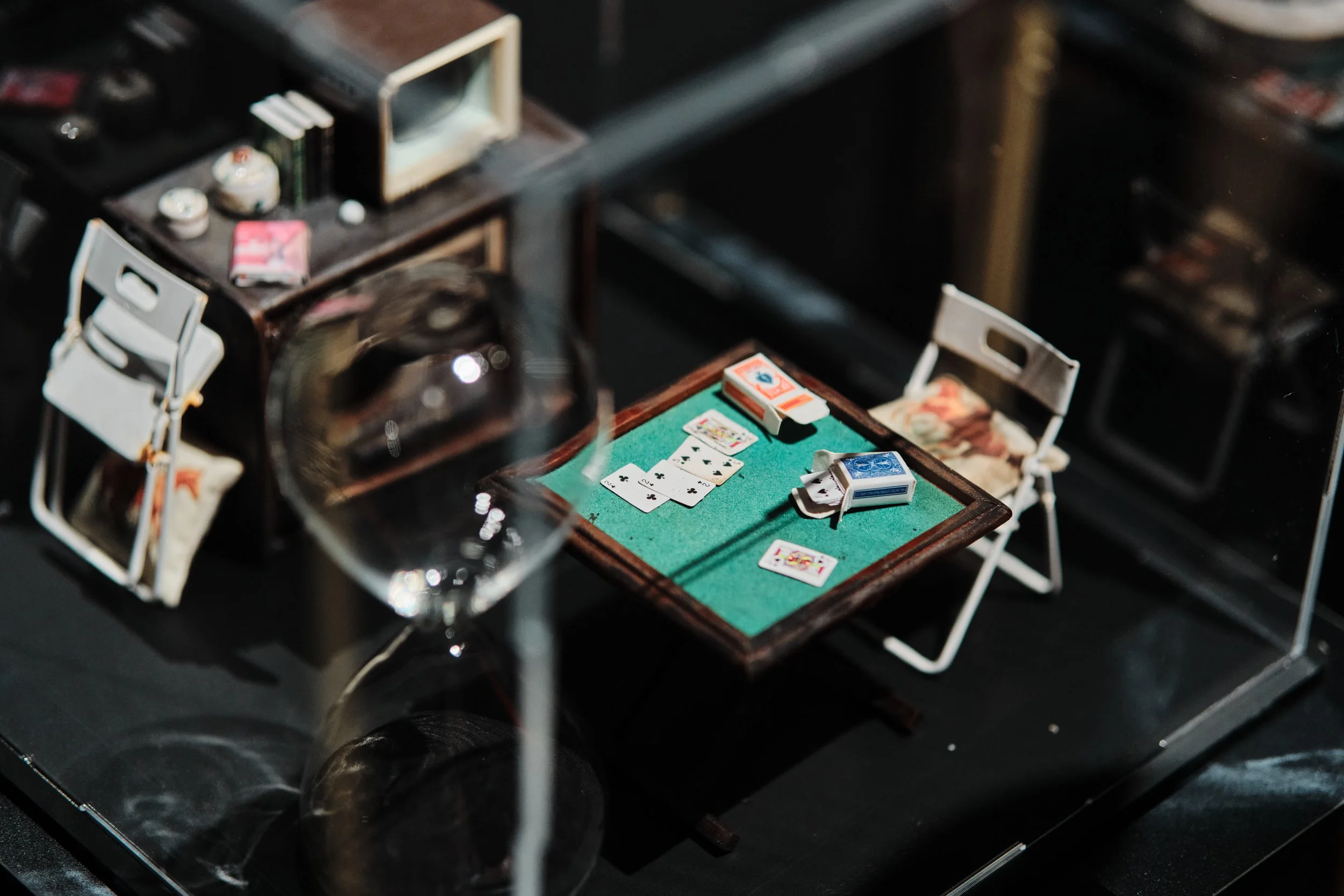

This summer, ArtHouse Jersey presents Fallowfield, an emotionally layered and visually arresting solo exhibition by Jersey based artist Clare Ormsby. Running until 24 August 2025 at Capital House gallery in St Helier, the exhibition is a transformative journey through memory, decay and creative rebirth. At its heart is the haunting narrative of a Victorian style doll’s house, meticulously constructed, left to the elements, and ultimately destroyed by fire, a process Ormsby documented over several years. Out of its ashes rises Fallowfield: a compelling blend of life sized installations, sculpture and film that invites audiences to reflect on abandonment, resilience, and the spaces we carry within us.

We caught up with Clare to learn more about her creative process, the story behind Fallowfield, and what visitors can expect from this immersive exhibition.

Fallowfield is a deeply personal project. Can you tell us where the idea first came from and how it evolved over time?

I can’t remember exactly when I started thinking about the concept of Fallowfield. I would guess around three years ago. It came as a word that would just pop into my mind from time to time, then gradually it was there all the time, gently bouncing around like a screensaver. Next came a few words: “Your dreams aren’t gone, just lain too long, sleeping deep, beneath your feet, in the Fallowfield.” Then it became an abstract painting of the same name, whereby I painted (embedded) the words into the design and grew the rest of the painting around it. This was actually what I originally pitched to ArtHouse Jersey, but it wasn’t what they were looking for although it’s something I would still like to exhibit eventually. I also pitched various other things that I had tried to do, but none of them led to a whole body of work, they all reached dead ends. ArtHouse rejected those ideas but showed interest in my photographs of my abandoned doll’s house interior, which kickstarted the whole project. And the rest, so they say, is history.

The exhibition centres around a doll’s house you built and eventually set alight. What drew you to this object as a storytelling device?

I was originally drawn to create my own miniature urbex experience but subconsciously I was drawn to the symbol of the burning house as it represents very strongly what I needed in my personal, creative life, ideas of cleansing and purification, liberation, the destruction of trauma, burnout and turmoil.

You mention being inspired by the abandoned homes of post industrial Detroit and Heather Benning’s conceptual art. What influence did these sources have on your own process?

The story of the boom and bust of Motor City Detroit and its subsequent abandoned McMansions perfectly encapsulates what happens when we force grow anything. It’s too much, too soon, there’s no integrity or infrastructure, and therefore no resilience nor strength to survive. In its wake is a sad and fascinating trail of lost lifestyles and livelihoods, crushed dreams and broken promises. How could anyone not be inspired by peering into this devastated microcosm of relatively recent history?

Heather Benning’s Dollhouse project (2005 to 2013) I can’t remember when or how I first came across it but again, it’s so unspeakably evocative. The way she plays with scale is deeply inspiring, and of course the seed was sown that Fallowfield’s demise had to be through fire too. What appeals about Benning’s house burning, and the beautiful 2014 Chad Galloway film The Dollhouse, is that it’s not an arson attempt on a disused building. It’s a ceremonial farewell. There is a ritual and a respect, as opposed to a negative destructive force. It’s a passageway forward to another existence even if that means being particles of ash or dust. After all, without those we would not have the beautiful soft focus views of sunsets.

The title Fallowfield suggests both a literal and metaphorical meaning. What does that word represent to you personally?

Literally, Fallowfield (not the area of Manchester and its university residential halls campus) is the field that’s having a rest. It looks like it’s doing nothing, whilst all the other fields are displaying their crops. Fallowfield appears empty, but beneath the surface, out of sight, it’s slowly regenerating. Earthworms are reoxygenating the soil and the depleted nutrients are returning. Time and nature are working their magic. The magic of mundane circadian miracles.

Metaphorically, transitioning from feeling like the empty vessel to living as the Fallowfield creatively saved me. In many ways, it was that lightbulb moment of realising that time and nature could work their magic on me too. In resting, I could recover my fertile imagination again and generate something to show and share.

You speak of a “decade of creative silence.” How did working on Fallowfield help you navigate or overcome that period?

It was torturous for me to have been stripped of my ability to daydream and create in the preceding years. I felt so empty and had no escapism nor therapy. Fallowfield has been a gift of a project. I could take my time to form my ideas, to rebuild, and to learn and try new techniques and mediums. Aside from the Shou Sugi Ban, I’d never tried cyanotype printing before, nor hair weaving, candle making, flower pressing, automatic writing, wallpapering... Take care of the processes and the results will take care of themselves. I like being in my own world and can get derailed very easily if someone starts critiquing what I’m doing whilst it’s still in progress. But ArtHouse let me develop Fallowfield how I wanted to, so once I’d started, I had total creative freedom to be absorbed in the project and go wherever it took me. I would go with “navigate” rather than “overcome” as I can never take for granted what will or will not come next.

Nature gradually reclaiming the doll’s house seems to play a central role in the work. What did you discover during that period of slow observation and decay?

Nature reclaiming manufactured places and objects is curious. No one likes damp or mould in their own homes but when you look at areas like Chernobyl, human absence lets nature recover. Forty years after the worst nuclear accident in our history, the area is teeming with wildlife. It is now one of Europe’s largest nature reserves. Nature becomes more resilient.

The birds loved the house, and I loved the birds. All the birds got along well with each other because the small birds such as sparrows, robins, finches and bluetits could go inside to eat, whilst the larger ones like pigeons, crows and magpies could eat from the roof and doorways. So there was no bird bullying.

How did the final burning of the house feel, creatively, emotionally, symbolically? Was it difficult to let it go?

The burning of the house was nerve wracking. One chance to burn. One chance to film. Fire (like the birds) is impossible to direct, so there were many key elements totally out of my control. Fortunately, it burnt well. There was also a good amount of wind that day, with occasional gusts, which made the fire behave spectacularly.

I was sad to see the house go. It was always fated to burn, it was just a matter of choosing when. But in many ways, it hasn’t gone, it’s entered a new chapter. So I haven’t let go just yet.

The exhibition includes life sized recreations of the doll’s house interiors using charred wood, vintage ephemera, and the Japanese technique of Shou Sugi Ban. What was it like translating something so small and fragile into full scale installations?

Working site specifically for the Capital House gallery meant I had a fair amount of space to fill, so I was always going to reinterpret the miniature as life size. But I didn’t want to literally recreate the doll’s house rooms. I wanted to reinterpret the spaces in a fine art style. I was not explicitly aware of Shou Sugi Ban when I started researching burnt furniture. I’d admired the black cladding on buildings but not known exactly what it was. I actually considered originally making life size cardboard furniture, but the aesthetic wasn’t right and I wasn’t convinced by the process. So I started sourcing furniture (from Ecycle, Acorn and Durrell) that resembled the pieces in the miniature house. I would have just torched them and left it at that, except I had to find a way of stabilising the surface so that visitors to the gallery could interact with the exhibits without getting covered in charcoal. Shou Sugi Ban fulfilled all these requirements. I could also indulge myself by scouring eBay for certain antiques and knick knacks to complete each main exhibit’s narrative. There are also several items related to matches, smoking, snuff and burning which directly reflect the theme.

There’s a strong sense of atmosphere and memory in this work. Were there specific memories, dreams, or personal histories you were drawing from when creating these spaces?

There’s a picture in the postcard album on the desk of a painting called The Golden Scriptures by Armenian artist Hovsep Pushman. We had a print of it on our wall at home when I was a small child, and it always fired my imagination. It’s actually a still life, but I used to read it like it was a Night at the Museum. The aesthetic of it and the dreamlike ambiguity of the composition informs my own still life photographs. I’m trying hard to live my own beautiful life despite various traumas that have occurred, and so I’m using my ability to tap into an evocative atmosphere. For example, the feeling I get when I see a half demolished house, with a fireplace halfway up the wall and remnants of wallpaper. I imagine the past lives of the previous occupants. It speaks to me but in whispers and I’m trying to decipher what it’s saying. In short, this is a process of discovery and an attempt to heal.

You cite artists such as Ron Mueck, Edward Hopper and Paul Nash as influences. What elements of their work do you feel resonate with Fallowfield?

Ron Mueck represents scale, how scale makes us feel. His detailed sculptures of human beings, either gigantic or petite, are incredible, arresting and unforgettable. And I can’t quite put into words that feeling of resonance between size. Either we are made large or small in comparison to his work, which for me evokes feelings of vulnerability.

Edward Hopper represents urban loneliness and a sense of melancholic nostalgia, again I’m circling back to the Detroit abandonment.

Paul Nash was a landscape artist in the Great War. The comparison of his bucolic landscapes before the war with his war paintings, where dystopian shards of burnt trees puncture his canvases like dead obelisks. His work speaks volumes and is deeply moving, insightful and profoundly sad.

How did it feel returning to public exhibition after such a long hiatus, and why was now the right time?

Now is the right time because it happened. It’s actually been a relatively slow, gentle, organic process. I figured that if it was meant to be, it would happen. It was ArtHouse Jersey’s Head of Programme, James Tyson, who picked up the doll’s house interior photographs and told me he thought they were interesting, which boosted my confidence and things expanded from there. Having the project in my head for some considerable time, planning it and revising it. Drawing and redrawing the gallery floor plan. It felt great to finally be installing it and a little surreal to be making a daydream into a reality, especially with a small crew to help. Having other people recreating my ideas felt amazing and weird. Wallpapering also felt strange, as the wallpapers are identical to the 1 to 12 scale ones, so it was peculiar to have done that in both the doll’s house and the gallery.

I didn’t actually think about the public exhibition part of it in too much depth. I thought about successfully completing a project. We went straight from completing the install to the launch night. The launch was incredible. I thought perhaps 30 people would turn up, but the room was packed and the atmosphere was so positive, it was an unforgettable occasion for which I’m incredibly grateful. It was also quite the culture shock. My day to day life is quietly pottering around tinkering with things and living in my own head. Suddenly there were so many people to engage with. I don’t think I’ve ever done so much talking in my whole life. So scary but also wonderful.

What do you hope visitors will take away from Fallowfield, emotionally, aesthetically, or even spiritually?

I hope that visitors will feel how I feel when I visit an exhibition that really resonates with me or see something creative that deeply inspires me. I would love for visitors to feel amused, engaged, intrigued, refreshed. To feel like their day had been enriched in some small way because they stopped by. That would be amazing and gratifying. The overarching narrative on which hangs the whole of the Fallowfield experience is really a message of hope. A nod to just keep going, especially when one feels devastated and laid low. Despite everything, it is possible to build a beautiful existence out of the ashes of destruction.